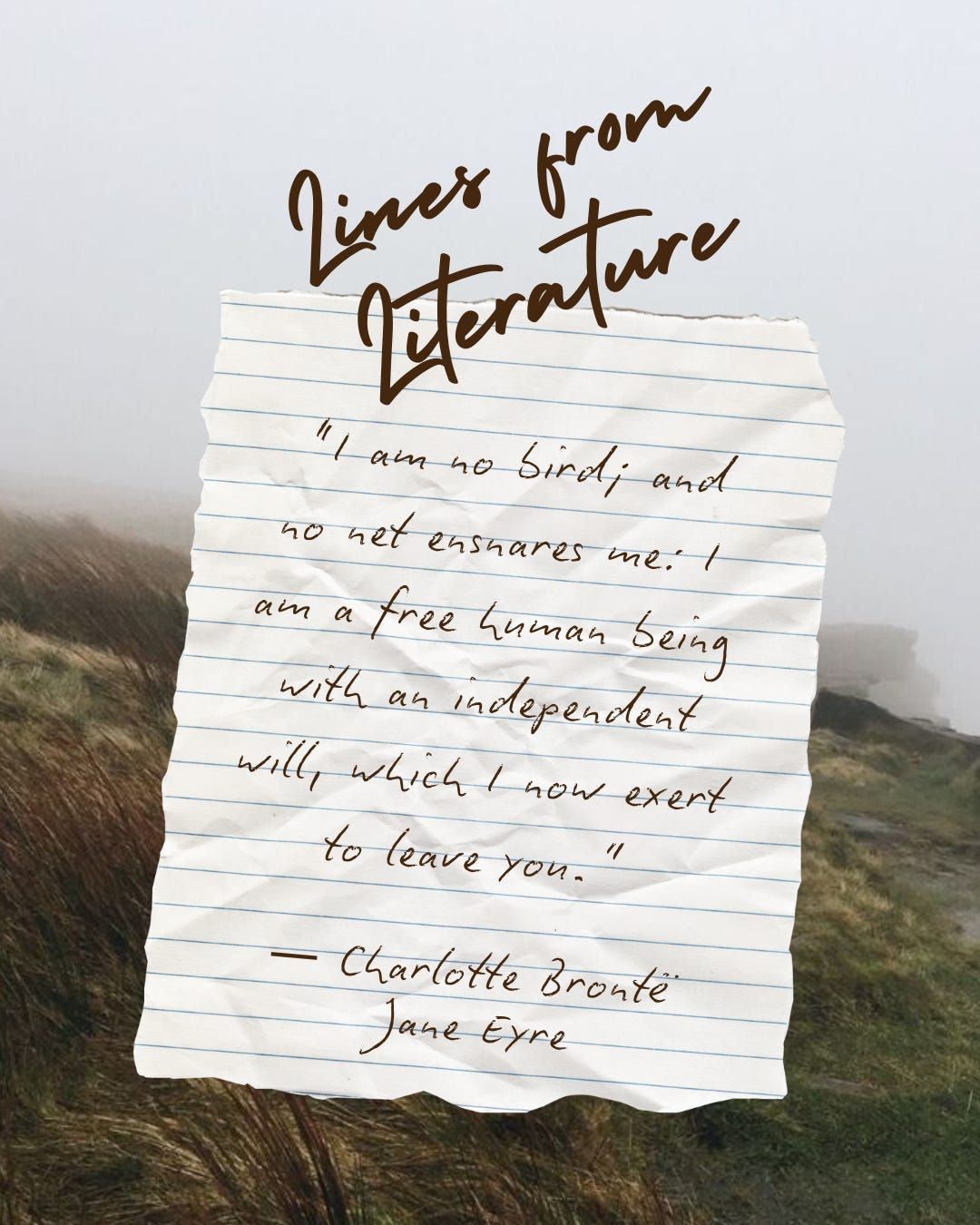

A few lines from some of my favourite writers, past and present. This week I’m taking inspiration from Charlotte Brontë’s Jane Eyre.

Charlotte Brontë’s Jane Eyre is a captivating tale of resilience, self-discovery, and defiance against societal constraints. Orphaned at a young age and raised in the oppressive household of her aunt, Jane endures a harsh childhood before finding solace at Lowood School, where she cultivates her intellect and sense of independence.

As a young woman, Jane secures a position as a governess at Thornfield Hall, where she meets the enigmatic Mr. Rochester. Their deep and passionate connection is tested by secrets lurking within Thornfield’s walls, forcing Jane to confront her values, desires, and sense of self-worth. Refusing to compromise her principles, she embarks on a journey of self-reliance, ultimately discovering love and belonging on her own terms.

Jane Eyre is a richly woven tale of transformation and inner strength, centering on a woman’s quest for autonomy in a world dominated by rigid social hierarchies. Brontë’s evocative prose and deeply personal characterisation breathe life into Jane, making her a fully realised, complex heroine.

Novels like this seem to be more important than ever right now - I highly recommend it to anyone who loves Gothic romance, feminist literature, and timeless stories of self-empowerment.

📖 Purchase Jane Eyre by Charlotte Brontë here

The Brontë Sisters At London’s National Portrait Gallery By Patrick Branwell Brontë

The Brontë Sisters is a famous group portrait painted by Patrick Branwell Brontë, the only brother of Charlotte, Emily, and Anne Brontë. Created around 1834, the painting depicts the three literary sisters seated in a row, dressed in modest clothing, with solemn expressions. Originally, Branwell included himself in the portrait but later painted over his own figure, leaving behind a faint outline of his presence between Emily and Charlotte. This ghostly trace adds an eerie quality to the artwork, symbolising his absence and later struggles.

Remarkably, the painting was discovered years later, discarded on top of a wardrobe in Haworth Parsonage, the Brontë family home. Forgotten and neglected, it was eventually recognised for its historical significance and later housed in London’s National Portrait Gallery. Today, it remains one of the most iconic visual representations of the Brontë family, offering a rare glimpse into their shared world before their literary fame.

The figures in this painting (Anne on the left, Emily in the centre, and Charlotte on the right) are identified by Mrs Gaskell's famous description of it

(Life of Charlotte Brontë, 1914, p 135):

'I have seen an oil painting of his, done I know not when, but probably about this time (1835). It was a group of his sisters, life size, three-quarters length; not much better than sign painting, as to manipulation; but the likenesses were, I should think, admirable. I could only judge of the fidelity with which the other two were depicted from the striking resemblance which Charlotte, upholding the great frame of canvas, and consequently standing right behind it, bore to her own representation, though it must have been ten years and more since the portraits were taken. The picture was divided, almost in the middle, by a great pillar. On the side of the column which was lighted by the sun stood Charlotte in the womanly dress of that day of gigot sleeves and large collars. On the deeply shadowed side was Emily, with Anne's gentle face resting on her shoulder. Emily's countenance struck me as full of power; Charlotte's of solicitude; Anne's of tenderness.'

In a letter describing her first visit to Haworth in 1853, Mrs Gaskell made one further comment on the portrait (Life, 1914, p 619):

'One day Miss Brontë brought down a rough, common-looking oil painting done by her brother of herself - a little rather prim-looking girl of eighteen - and the two other sisters, girls of sixteen and fourteen, with cropped hair, and sad dreamy-looking eye.'

This would date the portrait to 1834. Until its discovery in 1914 it was thought that the portrait had disappeared or been destroyed. When Clement Shorter visited the Rev Nicholls at his home in Banagher, Ireland, in 1895, he came away with the impression that the NPG fragment, representing Emily, had been cut from the NPG group portrait, the rest of which had been destroyed. Shorter was not aware that both fragment and group portrait were lying upstairs on top of a cupboard, the group portrait having remained there apparently since Nicholls first moved to Ireland in 1861. Nicholls clearly did not want the portrait to become known, and it is surprising that it has survived. His antipathy was apparently shared by Charlotte Brontë, his first wife, who wrote, quite untruthfully, to Mr Williams in 1850 at the time when Agnes Grey and Wuthering Heights were being republished: 'I grieve to say that I possess no portrait of either of my sisters'. She did not want Branwell's portraits to be reproduced, though she was prepared to show them to Mrs Gaskell. When the NPG group portrait was discovered, it had been removed from its stretcher, and was folded in four (the fold marks are still clearly visible).

'I daresay you may wonder how I never said anything of the Portraits but till about six months ago I did not know they were in the House - They must have been put in a wardrobe (top) years ago & servants took down the panel, dusted it & put them back again but about six months ago, I was sitting in the room & my nurse was settling some things for me took down the panel and asked if I knew what was in it. I did not, so was much surprised.'

In a conversation at this time with her niece, Miss F. E. Bell, Mrs Nicholls remarked:

'"Your uncle disliked them very much", said Aunt Mary, "he thought they were very ugly representations of the girls, and I think meant to destroy them, but perhaps shrank from doing so - you see, there is only one other existing portrait of Charlotte, and none at all of Emily and Anne.”

In 1957, Miss Jean Nixon noticed in the group portrait the outlines of a figure underneath the pillar, which had been painted out. Infra-red photography revealed more clearly the figure of a man, almost certainly Branwell Brontë, who appears second from the right in the two other Brontë group portraits, the destroyed group from which the NPG fragment comes and the so-called 'Gun Group'. He is dressed in a black coat and cravat, and a white shirt, and apparently fits Charlotte's description of her brother, written in the introduction to one of the Angrian stories of 1834: 'A low slightly-built man attired in a black coat ... a bush of carroty hair so arranged that at the sides it projected almost like two spread hands ... black neckerchief arranged with no great attention to detail'.

It is not known why he painted himself out, unless he felt the composition was too cramped with four figures. There is no evidence for the theory that Branwell painted the portrait of his sisters on top of a canvas, which he had already used for the portrait of a man. The figure of the man is perfectly in scale with the other figures, and forms the logical apex of a triangular composition. The large, blurred pillar, is, as Dr Ingeborg Nixon suggested, of uncertain significance, and this provided her and her sister with the first clue that there might be another figure underneath